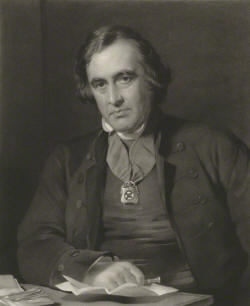

Richard

Chenevix Trench (9 September 1807 – 28 March 1886) was an Anglican archbishop

and poet. He was one of the original Cambridge

Apostles.

Richard

Chenevix Trench (9 September 1807 – 28 March 1886) was an Anglican archbishop

and poet. He was one of the original Cambridge

Apostles.Queer Places:

Harrow School, 5 High St, Harrow, Harrow on the Hill HA1 3HP

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Westminster Abbey

Westminster, City of Westminster, Greater London, England

Richard

Chenevix Trench (9 September 1807 – 28 March 1886) was an Anglican archbishop

and poet. He was one of the original Cambridge

Apostles.

Richard

Chenevix Trench (9 September 1807 – 28 March 1886) was an Anglican archbishop

and poet. He was one of the original Cambridge

Apostles.

He was born in Dublin, Ireland, the son of Richard Trench (1774–1860), barrister-at-law, and the Dublin writer Melesina Chenevix (1768–1827).[1][2] His elder brother was Francis Chenevix Trench.[3] He went to school at Harrow, and graduated from Trinity College, Cambridge in 1829.[4] In 1830 he visited Spain.[5] While incumbent of Curdridge Chapel near Bishop's Waltham in Hampshire, he published (1835) The Story of Justin Martyr and Other Poems, which was favourably received, and was followed in 1838 by Sabbation, Honor Neale, and other Poems, and in 1842 by Poems from Eastern Sources. These volumes revealed the author as the most gifted of the immediate disciples of Wordsworth, with a warmer colouring and more pronounced ecclesiastical sympathies than the master, and strong affinities to Alfred Lord Tennyson, John Keble and Richard Monckton Milnes.[6] In 1841 he resigned his living to become curate to Samuel Wilberforce, then rector of Alverstoke, and upon Wilberforce's promotion to the deanery of Westminster Abbey in 1845 he was presented to the rectory of Itchenstoke. In 1845 and 1846 he preached the Hulsean lecture, and in the former year was made examining chaplain to Wilberforce, now Bishop of Oxford. He was shortly afterwards appointed to a theological chair at King's College London.[6] Trench joined the Canterbury Association on 27 March 1848, on the same day as Samuel Wilberforce and Wilberforce's brother Robert.[2] In 1851 he established his fame as a philologist by The Study of Words, originally delivered as lectures to the pupils of the Diocesan Training School, Winchester. His stated purpose was to demonstrate that in words, even taken singly, "there are boundless stores of moral and historic truth, and no less of passion and imagination laid up"—an argument which he supported by a number of apposite illustrations. It was followed by two little volumes of similar character—English Past and Present (1855) and A Select Glossary of English Words (1859). All have gone through numerous editions and have contributed much to promote the historical study of the English tongue. Another great service to English philology was rendered by his paper, read before the Philological Society, On some Deficiencies in our English Dictionaries (1857), which gave the first impulse to the great Oxford English Dictionary.[7] Trench envisaged a totally new dictionary that was a 'lexicon totius Anglicitatis'.[8] As one of the three founders of the dictionary, he expressed his vision thus: it would be 'an entirely new Dictionary; no patch upon old garments, but a new garment throughout'.[9] His advocacy of a revised translation of the New Testament (1858) helped promote another great national project. In 1856 he published a valuable essay on Calderón, with a translation of a portion of Life is a Dream in the original metre. In 1841 he had published his Notes on the Parables of our Lord, and in 1846 his Notes on the Miracles, popular works which are treasuries of erudite and acute illustration.[6] In 1856 Trench became Dean of Westminster Abbey, a position which suited him. Here he introduced evening nave services. In January 1864 he was advanced to the post of Archbishop of Dublin. Arthur Penrhyn Stanley had been first choice, but was rejected by the Irish Church, and, according to Bishop Wilberforce's correspondence, Trench's appointment was favoured neither by the prime minister nor the lord-lieutenant. It was, moreover, unpopular in Ireland, and a blow to English literature; yet it turned out to be fortunate. Trench could not prevent the disestablishment of the Irish Church, though he resisted with dignity. But, when the disestablished communion had to be reconstituted under the greatest difficulties, it was important that the occupant of his position should be a man of a liberal and genial spirit.[6] This was the work of the remainder of Trench's life; it exposed him at times to considerable abuse, but he came to be appreciated, and, when in November 1884 he resigned his archbishopric because of poor health, clergy and laity unanimously recorded their sense of his "wisdom, learning, diligence, and munificence." He had found time for Lectures on Medieval Church History (1878); his poetical works were rearranged and collected in two volumes (last edition, 1885). He died in London, after a lingering illness. From 1872 and during his successor's incumbency the post of Dean of Christ Church, Dublin was held with the archbishopric. He died on 28 March 1886 at Eaton Square, London, and was buried at Westminster Abbey.[2] George W. E. Russell described Trench as "a man of singularly vague and dreamy habits" and recounted the following anecdote of his old age: He once went back to pay a visit to his successor, Lord Plunket. Finding himself back again in his old palace, sitting at his old dinner-table, and gazing across it at his wife, he lapsed in memory to the days when he was master of the house, and gently remarked to Mrs Trench, "I am afraid, my love, that we must put this cook down among our failures."[10]

My published books: